We can help you with that awkward, annoying injury. Whether its a twisted ankle, sore neck or just some aches and pains in you muscles and joints. Call us now and get moving again.

08.11.2018

Abel Tasman National Park

From October 21 to October 28, 20 clients and friends of Bangalow Physiotherapy travelled to Abel Tasman National Park for a 50km hike. We had a lovely time with minimal injuries, before being wined, dined and guided by the ever-so-gracious Wilson Abel Tasman. For two nights, we stayed in two different locations as we “stamped” our way through the park.

We were initially ferried to our starting location, passing some adorable seals sunning themselves on an island. We also enjoyed the native birdlife on offer in the park.

On two different days, in two different locations, some of us took up kayaking in the glorious estuaries – others decided to sea kayak (with plenty more sightings of seals). And some of us simply enjoyed the tranquil offerings of the local walking tracks. A wonderful trip to remember.

Awaroa Bay

Torrent Bay Lodge – view from the track

Kim at Cleopatra’s Pool

Beach near Torrent Bay

Kayaks near Cleopatra’s Pool

Rosemary and Kim on a nature walk

Suspension Bridge

24.09.2018

The Role of Inflammation

What is inflammation?

Inflammation is the response to a soft tissue injury that results in the release of inflammatory chemicals (known as inflammatory cytokines) into the tissue. These chemicals create an inflammatory cascade, seeing the infiltration of a variety of cells that, like most other cells, convert oxygen into energy (fuel) in order to work to clean up damaged tissue and others that build new tissue. Inflammation is the first important element of tissue healing where clotting occurs and cells are recruited to clean up and repair the site. The inflammatory phase usually lasts 7-10 days.

5 cardinal signs of inflammation:

- Heat

- Swelling

- Redness

- Pain

- Function loss

Retrieved 5/9/18 from: https://www.britannica.com/story/how-is-inflammation-involved-in-swelling

When does inflammation occur?

In the context of physical activity, inflammation occurs after injury or insult to the soft tissues of the body, whether that be an external object that breaks the skin, or from overuse of a limb causing unnecessary internal stretch, friction or compression of a structure, such as a tendon. For example, if you were to roll your ankle during a game of soccer, your ankle ligaments may be stretched beyond their normal limits and become torn or ruptured (i.e. spained). It is this damage that releases and activates the first inflammatory chemicals that set of the inflammatory cascade.

Causes:

- Direct blow (e.g. fall or collision with another object/person)

- Overstretching of ligaments/tendons/muscles/skin (e.g. ankle inversion injury aka ‘rolled ankle’)

- Friction (e.g. with repeated movement: tendon-on-bone, bone-on-bone)

- Penetrating object (e.g. stick through skin)

Is inflammation good or bad?

In the right context, inflammation is a good thing to an extent as it plays an important role in initiating tissue repair. Without it, it would be difficult for our tissues to repair efficiently. Rather than trying to halt the process, it is best to work to manage it appropriately.

Management:

Historically, initial treatment of soft tissue injury and inflammation has been RICE – Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation. However, evidence has evolved to support a new acronym, MCE – Move safely, Compress, Elevate. This leaves out the need for ice, which allows the inflammatory response to work its magic, increasing oxygen-carrying blood to the area which the cells use as fuel to clear debris and repair damaged tissue. For pain relief, ice may be used immediately post injury, however, after the first hour the MCE rule should be applied.

For the same reason, it is suggested that you avoid anti-inflammatory medications (i.e. ibuprofen) during this time, instead opting for medications that work primarily to control pain.

Image retrieved 17/9/18, from: http://newhamburgwellnesscentre.blogspot.com/2013/09/rehabilitation-of-ankle-sprains_5317.html

A trained physiotherapist will help to establish safe range of movement in both the early stages, and moving forward as inflammation resolves. This helps to avoid unhelpful movement patterns as well as unnecessary stiffness and pain in the long-term, speeding up return to normal function.

LAZER (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) applied by a trained physiotherapist can assist the inflammatory stage during, as the beams work to more easily dissociate oxygen bound blood cells in the damaged area, so the healing cells have access to more oxygen (fuel) and therefore can work more efficiently and effectively.

Image retrieved 17/9/18, from: https://www.djostore.com.au/chattanooga-laser-therapy-module.html

See a physiotherapist to ensure appropriate and effective management of initial inflammation and a aid a faster recovery.

10.09.2018

Lateral Hip Pain

Lateral Hip pain that can run down the outside of the leg past the knee can occur due to a multitude of pathologies but it is collectively coined as Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS). The incidence of GTPS is between 1.8 and 5.6 per 1000/year making it quite a common problem. It is more common in women then men at a ratio of 4:1.

The Leap Trial which looked at the effects of three methods of treatment for GTPS was recently published in the British Medical Journal. Our clinical director Kim Snellgrove was involved in the Leap Trial as a treating physiotherapist when she worked for Alison Grimaldi in 2013/2014 and assisted with the education and exercise group.

The Leap Trial compared three groups over a 12 month period. There was a corticosteroid group, an education and exercise group and a wait and see group. At eight weeks it was found that the education plus exercise group and the corticosteroid group both reported a global improvement in their function and pain compared with the wait and see approach. The education and exercise group at 8 weeks actually performed better than the corticosteroid group. At 12 months education plus exercise showed better global improvement than the corticosteroid injection.

The education and exercise group was educated in ways to avoid compressive load to the lateral gluteal tendons. Participants posture and functional activities were corrected. Exercises involved progressive loading of the lateral gluteals commencing with a very gentle isometric program and progressing through a series of graded loaded exercises as the participant was able to tolerate the load. Reformers where also utilised in the later stage loading program in the Leap Trial.

If you are struggling with lateral hip pain at Bangalow Physiotherapy we can assist you using evidenced based rehabilitation and education.

References

Barratt, P., Brookes, N., Newson, A., Conservative treatments for greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016; 51 97-104 Published Online First: 10 Nov 2016. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095858

Grimaldi, A., Conservative management of lateral hip pain: the future holds promise http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096600

Mellor, R., Bennell, K., Grimaldi, A., Nicolson, P., Kasza, J., Hodges, P., Wajswelner, H., Vicenzino, B., Education plus exercise versus cortisosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1662 | BMJ 2018;361:k1662

10.09.2018

Extracorporal Shockwave Therapy (ESWT)

What is it?

You may have heard of the new machine we have in our clinic and are wondering what it is. It is a Shockwave Machine. There are two types of Shockwave, there is radial shockwave (RSW) which we have and there is focused shock wave (FSW). Radial Shockwave is ballistically generated by compressed air. Radial Shockwave is a broad wave that can penetrate up to 5-6 cm in depth where as focused shockwave has a deeper penetration up to 12 cm. In physiotherapy radial shockwave is utilised to treat the more superficial tendons.

Shockwave is like a pressure wave and is sometimes termed an acoustic stimulator which creates biological effects.

The biological effects of shockwave are:

- Shockwave induces proliferation, migration and differentiation of stem cells, which significantly contribute to tissue healing and regeneration.

- Shockwaves promote tenocyte proliferation and progressive tendon tissue regeneration and induce biomechanical responses that promote tendon remodelling in tendinopathies.

- Bone cells are also sensitive to mechanotransduction. Shockwave enhances osteoregeneration. It can acts on the bony and periosteal cells and aids in the building of bone interacting with osteoblasts and osteoclasts. It assists in neovascularization and matrix remodelling.

- Shockwave has been shown to be a immunomodulator in wound healing and tissue regeneration mainly through anti-inflammatory strategies.

- Shockwave is also considered to be analgesic (pain relieving) due to the interference to the nervous system.

- Shockwave is not utilised with acute injuries but rather with chronic conditions that require assistance in stimulating healing. It is therefore not utilised until after 6-8 weeks of an injury.

It has been found to be beneficial in the treatment of chronic:

- Achilles Tendinopathy

- Planter Fasciitis

- Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy

- Patellar Tendinopathy

- Adolescent Osgood Schlatters Disease

- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

- Calcific Tendinopathy of the Shoulder

- Coccydynia

- Lateral Epicondyalgia

- Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

Sazena et al found a 78.38% improvement in achilles tendinopathy after radial shockwave therapy up to one year later after 3 sessions. Combining shockwave therapy with traditional loading programs for achilles tendinopathies was found to have a significantly higher success rate than loading alone at 4 months (Rompe 2009).

Chang et al compared 12 randomized control trials and compared Focus Shockwave, Radial Shockwave and placebo. Radial Shockwave had the highest effectiveness versus placebo or Focus Shockwave in reducing pain in plantar fasciitis.

Cacchio et al utilised shockwave therapy on the chronic hamstring tendon of professional athletes and found 80% of the athletes in the shockwave group where able to return to sport after 9 weeks compared with 0% of the exercise alone group returning at 9 weeks. A greater number of participants in the shockwave group, i.e. 85 percent also reported more that a 50% reduction in pain at 3 months compared with the exercise group where only 10 % reported a 50% reduction in pain.

Patellar tendinopathy has also positively responded to radial shockwave therapy when used in combination with an eccentric training program (Van der Worp et al). Osgood-Schlatter Disease which is found in the adolescent and associated with growth spurts also effects the patella tendon. Shockwave has also been found to be of benefit with this condition (Lohrer et al).

In 2015 it was found that shockwave therapy helped reduce symptoms of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome when used in combination with night splints. There was significantly reduced pain and improved function versus the shame treatment with night splints (Wu et al).

Shockwave has also been found to be beneficial for lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow). Lateral Epicondylitis symptoms are reported in the lateral elbow with grip and lifting. After just one treatment of shockwave at 6 months follow up grip strength and reports of pain where found to be significantly improved (Spacca et al).

Calcific Shoulder Tendinitis has also been found to benefit from radial shockwave therapy (Cacchio et al)

Most studies recommend Shockwave as an adjunct to other physiotherapy treatments. It is generally expected that shockwave will be performed 1x per week for 3-7 treatments.

References

- Aqil, A., Siddiqui, M., Solan, M., Redfern, D., Gulati, V., Cobb, J., Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy is Effective in Treating Chronic Planterfasciitis: A Meta-analysis of RCTs.

- Cacchio., A., Paoloni., M., Barile A., Don, R., De Paulis., F., Calvisi, V., Ranovolo, A., Frascarelli., M., Santill., V., Spacca., G. Effectiveness of Radial Shock-wave Therapy for Calcific Tendinitis of the Shoulder: Single-Blind, Randomized Clinical Study. Physical Therapy 2006 May; 86(5): 672-82

- Chang, K., Chen, S., Chen, W., Tu, Y., Chien, K., Comparative Effectiveness of Focused Shockwave Therapy of Different Intensity Levels and Radial Shock Wave Therapy for Treating Plantar Fasciitis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 7/2012 93(7): 1259-68

- Cristina d’Agostino, M., Craig, K., Tibalt, E., Respizzi, S., Shockwave as biological therapeatic tool: From mechanical stimulation to recovery and healing, through mechanotransduction. Int J Surg. 11/2015

- Lohrer, H., Nauck, T., Scholl, J., Zwerver, J., Malliaropoulos, N., Extrocorporeal Shock Wave Therapy for Patients Suffering from Recalcitrant Osgood-Schlatter Disease. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 2012 Dec; 26 (4): 218-22

- Rompe, Furia, Muaffulli Eccentric Loading versus Eccentric Loading Plus Shock-wave treatment for Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy. A randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2009 Vol 37, No 3 P 463-471

- Saxena, A., Ramdath, S., O’Halloran, P., Gerdesmeyer, L., Gollwitzer, H., Extra-corporeal pulsed-activated therapy for Achilles Tendinopathy: a prospective study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(3):315-9

- Spacca, G., Necozione, S., Cacchio., A., Radial shock wave therapy for lateral epicondylitis: a prospective randomised controlled single-blind study. Eura Medicophys. 2005 Mar 41(1):17-25

- Vinding, J., Eaton, C., Shockwave Therapy in the Treatment of Musculoskeletal Disorders. DJO Publications 2016

- Van der Worp, H., Zverver, J., Hamstra, M., Van den Akker-Scheek, I., Diercks, R.L., No difference in effectiveness between focused and radial shockwave therapy for treating patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Athrosc. 2013 May

- Wu, Y., Ke M.J., Chou, Y., Chang, C., Lin, C., Li, T., Shih, F., Chen, L., Effect of radial shockwave therapy for carpal tunnel syndrome: A prospective randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Orthop Res. 2015 Nov

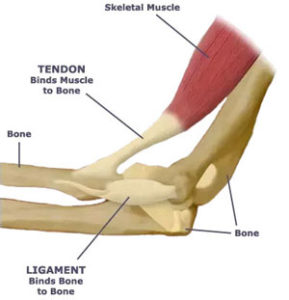

What is the tendon?

The tendon is made up of strong connective tissue found at the start (origin) and finish (insertion) of a muscle connecting the muscle to the bone ultimately allowing the muscle to contract, moving the bone and creating movement. Tendons are not to be confused with ligaments, which connect bone to bone in order to stabilise joints. Both tendons and ligaments are not elastic and are capable of withstanding incredible tensions as we walk, run, dance and jump.

(Figure taken 15/8/18 from: https://www.quora.com/What-are-t

endons-and-ligaments-and-what-are-they-composed-of)

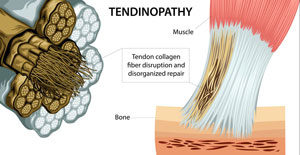

What is a Tendinopathy?

Tendonitis describes the condition in its early stages as inflammatory. After the initial stages, inflammation is no longer present and so the terminology of tendonitis should no longer be used. With tendinopathy, inflammation is no longer present. Instead, the tendon layout has been changed. When the tendon becomes overloaded by repetitive activities (e.g. jumping/running/hammering) or newly increased loading (e.g. increasing your running distance/pace dramatically), the fibres experience multiple microtraumas causing the release of inflammatory mediators. This causes the usually parallel-running tendon fibres to become disorganised. This disorganisation results in a newly thickened weaker tendon that is generally painful to touch and to load.

(Figure taken 29/8/18 from: http://chiroup.com/tendinopathy/)

Causes

- Repetitive activity – most often of energy storing activities (eg. jumping, running, hitting a tennis ball with a racquet, swinging a hammer)

- Increased loading

- Overuse

- Prolonged compressive force on the tendon

Signs & Symptoms

- Pain over the region of the tendon

- Pain extending into the muscle belly of the tendon

- Reduced strength

- Pain with contraction of the muscle (especially with energy storing activities)

- Tendon thickening

- Start-up pain with activity that can subside after a short amount of time during the activity

How to treat it?

Rest is not the cure – While symptoms subside during periods of rest, tendinopathies do not resolve and symptoms resume as activity resumes.

Exercise – Evidence tells us that exercise is one of the most effective way to treat a tendinopathy. Properly prescribed exercises aim to progressively load the tendon as tolerated in order to restore strength and reduce pain.

Shockwave therapy – Newly emerging evidence supports the use of shockwave therapy for stubborn tendinopathies (especially for insertional achilles and gluteus medius tendiopathies) (Al-Abbad & Simon, 2013; Rompe et al, 2009 & 2008; Rasmussen, et al, 2008)

Avoid aggravating activities. Avoid stretching.

References:

Abate M, Gravare-Silbernagel K, Siljeholm C, et al.: Pathogenesis of tendinopathies: inflammation or degeneration? Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2009, 11:235.

Al-Abbad, H., & Simon, J. V. (2013). The effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on chronic achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review. Foot & ankle international,34(1), 33-41.

Cook J, Purdam C: Is compressive load a factor in the development of tendinopathy? British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2012, 46:163-168.

Malliaras P, Barton CJ, Reeves ND, Langberg H: Achilles and Patellar Tendinopathy Loading Programmes. Sports Medicine. 2013:1-20.

Rasmussen, S., Christensen, M., Mathiesen, I., & Simonson, O. (2008). Shockwave therapy for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial of efficacy. Acta orthopaedica, 79(2), 249-256.

Rompe, J. D., Furia, J., & Maffulli, N. (2009). Eccentric loading versus eccentric loading plus shock-wave treatment for midportion achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial.The American journal of sports medicine, 37(3), 463-470.

Rompe, J. D., Furia, J., & Maffulli, N. (2008). Eccentric loading compared with shock wave treatment for chronic insertional achilles tendinopathy: a randomized, controlled trial. JBJS,90(1), 52-61.

05.09.2018

Exercise Tips for Dancers

Physiotherapy Exercises

To Improve Your Pointe

Why is improving your pointe important?

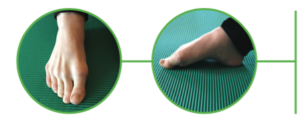

When you claw or flex your toes with your

pointe you overwork the long muscle that goes

to your big toe called Flexor Hallicus Longus.

Flexor Hallicus Longus can increase in size when

overused and impinge on the inside (medial) ankle

causing pain.

“By changing your pointe to long toes

instead of flexed toes you help to avoid

irritation to the Flexor Hallicus Longus

tendon.”

If you are planning on going enpointe or are

already enpointe it also helps to reduce blistering

of the toes if you pointe with long toes in your

pointe shoes.

How To Improve Your Pointe

Pointe Range of 0-5 degrees is desirable for

dancers. Some dancers are very mobile and find

it easy to have this range whilst others may have

some restrictions that a physiotherapist could

assist with gaining.

Regardless of whether you have a very mobile

foot or restricted mobility of your pointe the

following strengthening exercises will help you

to improve your pointe technique, active mobility

and stability of your pointe and prevent injury.

Your Measured Pointe Range Is: (Pointe range

between 0-5 degrees is considered desirable).

Doming

Whilst sitting on the ground place one foot on the

ground flat in front of you. Whilst keeping long toes

gently pull the arch up so as that you only flex at the

MCP joint in the foot as shown in the picture. Try to

keep the muscle at the front of the ankle called Tibialis

Anterior relaxed whilst you are doing this exercise.

Pointe Through Demi Pointe

Whilst in long sitting – start with your foot

dorsiflexed and then planterflex at the

ankle and then flex at the toes (MCP joint)

whilst maintaining long toes then return to

a dorsiflexed ankle. This exercise can also

be done with the use of a ball up against

the wall providing some resistance to the

movement.

Piano

is a toe articulation exercise that helps with awareness

of your toes and use of the small (intrinsic) muscles

found in your foot. Starting with your little toe try to

individually touch the floor with each toe until you

reach the big toe. Then go back to lifting the big toe

off first until each toe in turn is lifted off the ground

with the small toe being the last toe to lift off the

ground.

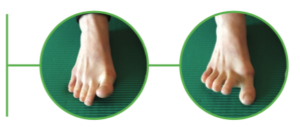

Toe Swapping

is another articulation exercise of the toes. In toe

swapping you try to lift the big toe off the ground

whilst the other toes remain stationary on the floor

and then you swap to try and lift the 4 outer toes off

the ground whilst the big toe stays on the ground and

then repeat.

Lower Back Pain and The Involvement of the Transverse Abdominals

The Transverse Abdominals (TrA) Muscle

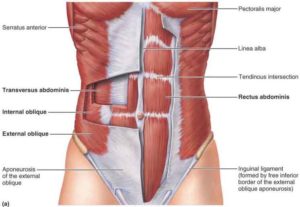

The TrA (aka. Transervaslis, or Transverse Abdominis) is known as the ‘corset’ muscle, as

it wraps around the abdominal region with fibres running in a transverse (horizontal) direction

with respect to the upright trunk. Looking at figure 1., you can see how it acts to enclose the

trunk cavity between the bottom ribs and the top of the pelvis. In the following image (figure

2.) you can visualise how deep the TrA runs to the more superficial muscles and fascia that

make up the rest of the abdominals (figure 2.)

(Fig 1. Image retrieved 1/8/18 from https://www.custompilatesandyoga.com/health/transverse-abdominis-learn-your-muscles/)

(Fig 2. Image retrieved 1/8/18 from http://theworkoutmama.com/tag/transverse-abdominis/)

The importance of TrA activation

In an asymptomatic patient, activation of TrA occurs just before there is movement in any

direction. This works to support the spine before movement occurs, reducing friction and

overstretching of the small joints between each vertebra (Saliba et al, 2010). Interestingly, TrA

activation has been found to be significantly delayed in patients with LBP (Hodges &

Richardson, 1996, and Selkow et al, 2017). This means that the preparatory bracing that

normally occurs before movement is significantly diminished or absent. A study conducted

by Kim et al (2013) utilised ultrasonography to detect the thickness (or bulk) of the TrA in

healthy subjects and subjects with lower back pain (LBP), finding notable muscle atrophy (or

shrinkage) of the TrA in the LBP group.

Evidence also supports the activation of TrA to reduce the joint laxity of the sacroiliac joint

(SIJ), the joint between your pelvis and the base of your spine (Richardson et al, 2002). This joint can cause pain and discomfort when it becomes lax, which can occur in many cases,

but especially in pregnant women due to the release of the hormone relaxin.

How do you improve the strength and activation of TrA?

The TrA muscle can be targeted using specific exercises and techniques that help to

stabilise the pelvis and spine. One such stabilisation method used includes the ‘drawing-in’

of the abdominals. Using this drawing-in technique, Teyhen et al (2005) was able to

demonstrate preferential activation of TrA. These types of stabilisation exercises have been

found to improve LBP and disability scores (Hosseinifar et al, 2013).

Selkow et al (2017) outlines certain exercises that have been shown to improve the onset of

activation of TrA by approximately 1 second before movement is initiated. This pre-activation

helps to train these deep core muscles to provide additional stability to the spine and pelvis

during daily movement, ultimately resulting in reduced pain and disability.These particular

exercises are also highly drawn on and create the basis for clinical pilates.

(Images from Selkow et al, 2017)

Clinical Pilates is based on these principles of correct and effective TrA activation to achieve

a neutral spine, encourage a strong, supportive base for which the limbs to function from,

reducing biomechanical dysfunction related issues and pain, and facilitating smooth and

pain-free movement in your daily life.

If you suffer from back, pelvic or hip pain, spinal instability is likely involved. A thorough

assessment by a trained physiotherapist will help to identify areas of potential dysfunction

and likely involvement of diminished TrA activation. Physiotherapist prescribed exercises

and physiotherapist-run Clinical Pilates can help to greatly alleviate acute and chronic pain

through the strategic and appropriate application of evidence based pilates postures and

exercises.

References

- Hodges, P. W., & Richardson, C. A. (1996). Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine, 21(22), 2640-2650.

- Hosseinifar, M., Akbari, M., Behtash, H., Amiri, M., & Sarrafzadeh, J. (2013). The effects of stabilization and McKenzie exercises on transverse abdominis and multifidus muscle thickness, pain, and disability: a randomized controlled trial in nonspecific chronic low back pain. Journal of physical therapy science, 25(12), 1541-1545.

- Kim, K. H., Cho, S.-H., Goo, B.-O., & Baek, I.-H. (2013). Differences in Transversus

Abdominis Muscle Function between Chronic Low Back Pain Patients and Healthy Subjects at Maximum Expiration: Measurement with Real-time Ultrasonography. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 25(7), 861–863. http://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.25.86 - O’Sullivan, P. (2005). Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders:

maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Manual therapy, 10(4), 242-255. Richardson, C. A., Snijders, C. J., Hides, J. A., Damen, L., Pas, M. S., & Storm, J. (2002). The relation between the transversus abdominis muscles, sacroiliac joint mechanics, and low back pain. Spine, 27(4), 399-405. - Saliba, S. A., Croy, T., Guthrie, R., Grooms, D., Weltman, A., & Grindstaff, T. L. (2010). Differences in Transverse Abdominis Activation with Stable and Unstable Bridging Exercises in Individuals with Low Back Pain. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy : NAJSPT, 5(2), 63–73.

- Selkow, N. M., Eck, M. R., & Rivas, S. (2017). TRANSVERSUS ABDOMINIS ACTIVATION AND TIMING IMPROVES FOLLOWING CORE STABILITY TRAINING: A RANDOMIZED TRIAL. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 12(7), 1048–1056.

- Teyhen, D. S., Miltenberger, C. E., Deiters, H. M., Del Toro, Y. M., Pulliam, J. N., Childs, J. D., … & Flynn, T. W. (2005). The use of ultrasound imaging of the abdominal drawing-in maneuver in subjects with low back pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 35(6), 346-355.

Bangalow Summer 6’s has been going for 6 weeks now and Kim Snellgrove the new owner of Bangalow Physiotherapy has been on the side lines every week giving advice and education to the teams and to perform some pre game taping. As prevention is the best cure we thought it might be helpful to discuss some of the ways we can help prevent soccer injuries.

Most of the taping pre game has been to ankles. This is recommended for high level activity after you have previously had an ankle sprain and helps to prevent recurrence.

There has also been a high prevalence of rectus femoris tears – which is one of the muscles of the quadriceps in the anterior thigh. This is a common football injury from kicking. Post injury management does differ dependent on severity of the injury but as a general rule icing in the first 2-3 days is still recommended as well as compression of the injury. You should also avoid stretching into pain. It is then beneficial to seek professional advice for ongoing management of your injury for optimal return to sport.

Some of the participants who experienced anterior thigh strains reported that they did not warm up or rushed there warm up which shows how important warm up can be to preventing injury. Warm up should include a general warming of the body with walking, then jogging and then active stretching. Active stretching involves movement of all joints of the body through their full range of motion as a movement rather than a static hold.

The PEP program which stands for Prevent Injury and Enhanced Performance has also been shown to assist in preventing soccer related injuries. It was developed by the Santa Monica Sports Medicine Research Foundation. When the PEP program was first trialed in 2002 it was found to reduce ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) tears in soccer players by 41%.

The PEP program should be performed three time per week. The PEP program takes about 15-20 minutes to complete. It involves 5 components:

- Warm Up – 30 seconds jog forward, 30 seconds side to side jog, 30 seconds backward jog

- Strengthening – Walk lunge one minute, Nordic Hamstrings 30 seconds, Single Heel Raises

- Plyometrics – two legged lateral jumps over a 5 cm high cone 30 seconds, then forward and backward jumps over the cone for 30 seconds.

- Agility – sprinting with emphasis on a three step deceleration

- Stretches – calf, hamstrings, quads and inner thigh

As we know prevention is the best cure, so before the next session of the Summer 6’s the participants might start a PEP program 4-6 weeks before the session. It is easily viewed on You-tube, but if you would like more advice you can find Kim at Bangalow Physiotherapy.

Gilchrist, J et al., Am J Sports Med. 2008 Aug;36(8):1476-83. doi: 10.1177/0363546508318188. A randomized controlled trial to prevent noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in Female Collegiate Soccer Players.

30.11.2017

What is dance physiotherapy?

There are two components to dance physiotherapy. There is the prevention and proactive screening of dancers and then there is the treatment of dance injuries and management of their rehabilitation back to full dance capacity.

Screening of dancers is commonly utilised prior to or at the commencement of placement into a dance school or company and prior to the adolescent dancer going enpointe. Screening helps to gain information about the dancer for the health professional, dance teacher or company to promote ongoing health and well-being of the dancer. The information gained from screening is utilised to create training programs to enhance strength, flexibility and fitness, all of which help to improve the skill of the dancer. Injury prevention strategies may also be prescribed from screening.

Adolescent ballet dancers generally around the age of 12 to 14 begin to desire to go enpointe. This transition to going enpointe provides a lovely window of opportunity to screen dancers. The pre-pointe assessment encompasses assessment of posture, functional skill level in dance and the ability of the dancer to maintain good core stability and lower extremity alignment. It also assesses the strength and flexibility of the spine, hips and ankles/feet. Years that the dancer has been dancing and the number of hours of dance the dancer is currently undertaking also influences whether the dancer is ready to go enpointe. Often after a pre pointe assessment is performed the young dancer is given a home program of massaging, stretching or strengthening to help her work on areas that need to be improved. For example, it is generally excepted that a young dancer prior to going enpointe can perform at least 20 single heel rises on both legs with good height and alignment.

Most dance injuries occur in the lower extremity and low back. The majority of lower extremity injuries occur in the ankle/foot with the hip coming in second. Ankle sprains are the most common ankle injury reported. Due to the dancer pointing they are also more likely to develop posterior impingement in the ankle then other sporting groups that can appear similar to Achilles tendonopathy symptoms. Dancers are more likely to injure the hamstring insertion from slow stretching than other sporting activities. Therefore, understanding the mechanism of injury and correctly diagnosing the injury is essential to rehabilitating the dancer as quickly as possible.

There are other factors that need to be considered when rehabilitating the dancer. The need to maintain strength and flexibility throughout the body so as they can return to pre-injury activities as soon as able. It is also important to be aware of the load the dancer places on their body with dance and the hours of dance to which they wish to return. Understanding that the dancer will need to be able to turn in a demipointe position or perform jumps and land from height from leaps onto a previously injured leg also helps to tailor rehabilitation. For example, with posterior impingement of the ankle this can be due to changes to the bone, or irritation to the posterior capsule or bursa. It could also be due to irritation to the flexor hallicus longus tendon. When returning to dance turning and jumping activities will need to be managed differently dependent on the structure that is causing the posterior symptoms.

Kim Snellgrove -About the Author – Kim spent the last year in Sydney working in a Dance Physiotherapy clinic working with the adolescent dancer, full time pre professional and professional dancers. She has been a physiotherapist for 26 years and returned to complete her Masters of Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy in 2012. In 2013 she also worked in Brisbane in a hip specialty clinic which has helped her immensely with treating the dancers hip. She returned to the Northern Rivers area in a full time capacity in March 2017 and looks forward to assisting dancers in this area from Bangalow Physiotherapy. Ph 02 6687 2330

References

Asking, C., Lund, H., Saartok, T., Thorstensson, A., Self reported hamstring injuries in student dancers. Scandanavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sport, 12/2002, 230-235

IADMS ( International Association for Dance Medicine and Science), The Challenge of the Adolescent Dancer. 2000

IADMS ( International Association for Dance Medicine and Science), Screening in a Dance Wellness Program. 2008

Jacobs, C.L., Hincapie, C.A., Cassidy, J.D., Musculoskeletal Pain and Injury in Dancers. A systematic review update. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science., Vol 16, No 2, 06/2012 74-84

Mayes, S., Foot and Ankle in Dance. 09/2016 ( Sue Mayes is the Senior Physiotherapist for the Australian Ballet)

Smith, P.J., MD., Gerrie, B.J., Varner, K.E. MD., McCulloch, P.C., MD, Lintner, D.M., Harris, J.D., MD, Incidence and Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Injury in Ballet. A Systematic Review. The Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 2015, 3 (7)

Wilmerding, M., Krasnow, D., Dancer Wellness. Human Kinetics 2017

Recent Comments