25.02.2020

Returning To Sport

When we return to sport, we often do this after an off season or an injury. At both times we are at greater risk of injury due to our downtime. I was once told by the physiotherapist for the Australian Ballet – Susan Mayes, that if a dancer in their company has 4 weeks holiday they would not expect them to be back to peak performance until 4 weeks after returning to classes and dancers at this level do not completely stop dancing in there “off time”. She then went on to explain that is why they do not have any performances immediately after the summer holidays. At an IADM (International Academy of Dance Medicine) conference that I attended several years ago, one presenter showed that the majority of back pain reported in DANCERS occurred in the beginning of the dancing year and there was less reports of back pain as the dance year progressed. This suggests that we are most vulnerable at the beginning of return to sport and also as we improve, fitness, strength, flexibility and skill over the course of training we often have less symptoms. Therefore, if we return more slowly to our chosen sport, we are less likely to injure.

Another way to avoid injury when returning to sport, is to perform agility skills for your sport in the offseason or before returning to sport. For example, SOCCER has the great FIFA11 program which has been shown to reduce ACL ruptures in elite players up to 45% and time off sport due to injury by up to 30 percent. FIFA 11 plus…. which the plus just means performing the program at the beginning and end of a training program has been shown to have even further benefits for soccer players in preventing injury. The FIFA 11 is a 20 minutes program that includes running, plyometrics (explosive exercises), strength and balance.

For more information click here.

Netball Australia has also introduced a knee prevention program. This program looks at good technique with take-off, learning how to correctly decelerate when running, and having good landing and change of direction skills. The KNEE program provided by netball Australia includes warm up, strength, balance/landing and agility sections. It is recommended that it is performed at least two time a week and before any court time.

Seeing a physiotherapist to screen you for flexibility, strength, balance, agility and functional skills specific to your sport prior to or at the beginning of the sporting season may help in preventing injury. Elite swimmers and AFL players are regularly screened to see if any deficits are occurring in their physical health. If strength reduces in an AFL players groin/ adductor contraction it has been shown they are more at risk of injury. Dancers have the pre-pointe assessment performed prior to going enpointe which is also a great screening tool for all dancers. At Bangalow Physiotherapy we are proficient in screening you prior to returning to sport and providing you with an individualised program targeted at your physical deficits.

In summary, if you have had time off from your sport, do not expect to be at peak performance and slowly build your endurance over the course of the first 4 weeks…. Or even better if you are involved in any running or agility sport have a go at the FIFA 11 program 2-3 x per week for 4 weeks prior to returning to sport. If you are unsure of what you should be working on, we are happy to help.

04.11.2019

Neck Pain

Neck pain can present itself in a myriad of different ways. It can be the result of whiplash after a car accident or of unknown causes, i.e. “I just woke up like this”.

Pain coming from neck structures can refer to the head causing headaches, or down the arms, or even further down the spine into what is known as the thoracic spine. The symptom of dizziness can also have its origins from the neck. If they are inflamed or compressed, the nerves of the neck can also cause symptoms of pain in the arms. Nerve pain is often combined with the symptoms of pins and needles and numbness and is often a sharp shooting pain. When the neck itself is referring pain down the arm it tends to be more of a dull ache.

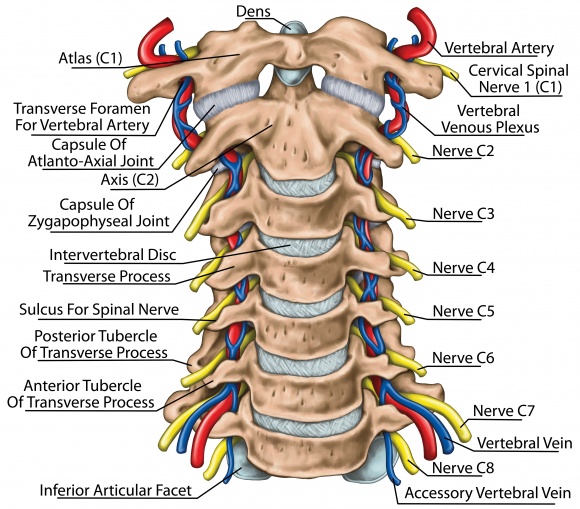

Let us start by looking at the anatomy of the neck, or cervical spine.

The neck is also referred to as the cervical spine. The cervical spine is comprised of seven bones called vertebrae. The vertebrae are numbered from C1 to 7 as they descend through the neck. The articulation of the bottom of the skull called the occiput and the first cervical vertebrae called the atlas forms the first joint in the spine called the atlanto-occipital joint. We often number the joints of the spine so the atlanto-occipital joint is numbered C0-1. A nodding action mostly occurs at this joint allowing the YES action of our neck. The top two vertebrae of the cervical spine are called the atlas (C1) and axis (C2). They allow – through their articulation on a peg-like, bony structure called the dens – a large portion of the neck’s rotation or the “NO action” of the neck.

Approximately 50% of the cervical spine’s rotation occurs at C1-2 and a third of nodding occurs at C0-1. The vertebrae from C3 to C7, and even down into the top of the Thoracic spine to T4, provide the remainder of the movement of the neck, forward/backward (flexion/extension), rotation, and side bending (lateral flexion).

All of the cervical spine bones have lateral facet joints that help to control the movement of the neck. From C2-3 down the spine, we also have discs between each vertebra. Ligaments also help to control the movement of the cervical spine as well as the musculature of the spine. Problems in the cervical spine from C0-3 can be the source of headaches. Whilst C5-T2 can refer pain down the arm. The cervical discs can also refer pain into the thoracic spine. This is termed the Cloward sign. The nerves of the neck can also be a source of symptoms which we will discuss in a further blog.

When a physiotherapist assesses your neck, they are going to be looking at the referral pattern of your pain and whether it matches your symptoms. We perform both active and passive movements of your spine to determine pain and stiffness. Passive movement of the spine is often called mobilisation of the spine. We massage the musculature of the spine to feel for overactivity. We check for ligamentous stability. We assess whether you have neural pain or referred pain.

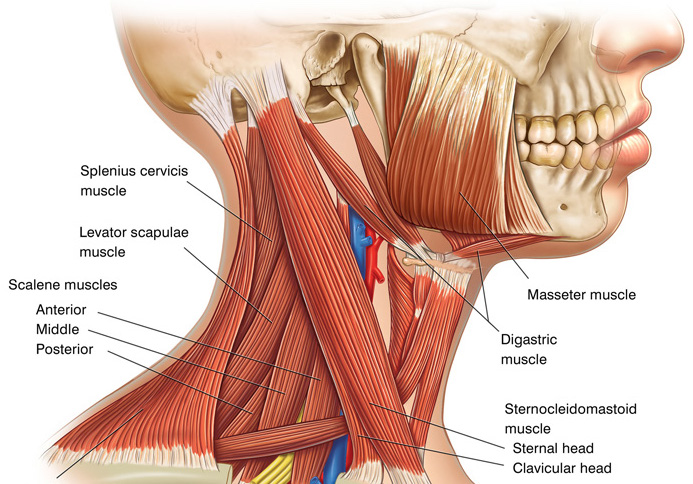

We also look at your posture whether you hold your head too far forward or your shoulder blades are rounded forward. The upper trapezius can sometimes appear tight when actually it is lengthened due to poor shoulder blade positioning. The position of the neck and shoulder blades influences mostly the musculature but also the loading of all the structures of the cervical spine and therefore is important to consider in the management of your neck pain. Any weakness of the cervical musculature is also important to assess.

Jull, G., Sterling, M., Falla, D., Treleaven, J., O’Leary, S., Whiplash, Headache and Neck Pain Research-based directions for physical therapies Churchill Livingstone Elsevier 2008

23.07.2019

Clinical Therapeutic Exercise

What is Clinical Therapeutic Exercise (CTE):

Essentially a set of tailored physical movements, Clinical Therapeutic Exercise is designed to improve your musculoskeletal function and establish an optimal state of well-being. Combining pilates and yoga with health and exercise science, the exercises vary from localised movements targeting specific muscles and limbs to those which engage the entire body. Used to return the convalescent back to peak physical condition and a healthy equilibrium, regular clinical therapeutic exercise can improve both physical and mental health.

Our Classes:

At Bangalow Physiotherapy, we offer two main types of CTE classes: mat and reformer. Mat classes offer lighter resistance than reformer classes however, less resistance doesn’t necessarily mean the exercises are less difficult. We incorporate body weight exercises into all our mat classes to help you the form long, lean and toned muscles that are essential to improving posture, balance and core strength. The reason reformer classes tend to be more comprehensive than mat classes is because using a reformer bed unlocks a greater variety of exercises that can be carried out from multiple different body positions. This really helps target the smaller muscle groups that can be otherwise difficult to engage.

Individual sessions:

During our private individuals our physiotherapists will help you to develop a personalised regime, addressing your particular needs and/or problem areas. Available by appointment from Monday to Friday, individual sessions will involve the use of various Pilates and other exercise equipment.

Group classes:

Attending our Physio guided group classes is a great way to establish healthy fitness regime. We have purposefully kept our classes small, limiting our classes to six people at at a time. This creates a safe and supportive environment and enable our teachers to devote more time to each person in the class, ensuring they get the very best guidance and personal assistance. With such personalised tutelage, beginners attending 2-3 sessions are able improve quickly, gaining an insightful understanding of their practice and limitations. See our timetable for class times.

Getting Started:

No matter your age or fitness level, our instructors and therapists are able to tailor the exercises to suit your personal needs. At bangalow Physiotherapy, our Clinical Therapeutic Exercise classes are carried out in 5 weeks blocks. For all new Clinical Therapeutic Exercise attendees, it is required that you have a 30min Clinical Therapeutic Exercise assessment before starting a course which you can book here. If you are unable to commit to a Clinical Therapeutic Exercise course of 5 weeks, you may opt to be a casual attendee. Whether you partake in one of our group or private classes, you will be under the careful supervision of our highly-qualified therapists who will tailor you a regime that suits your age, fitness level and injuries.

Health Fund Rebates:

23.05.2019

Runner’s Knee: How Your Physio Can Help

Contrary to what the name suggests, runner’s knee can affect anyone in the population regardless of their age and how often they don their joggers.

Interestingly, runner’s knee is not actually a specific injury, but rather a blanket term that covers the pain associated with a number of different issues. Patellofemoral pain – the medical term for runner’s knee – is attributed to a number of different issues ranging from overuse of the knees, a malalignment of the leg bones, foot problems, weak or unbalanced thigh muscles, and Chondromalacia patella, a condition in which the cartilage under your kneecap breaks down. When treating Patellofemoral pain, physiotherapists need to consider every possible factor in order to prescribe the right treatment.

Firstly, we need to look at muscle imbalances within the patient’s body. Perhaps certain muscles aren’t working as efficiently as they should be and the knee is overcompensating as a result. Poor gluteal control, for instance, is a major influence on your knee alignment when running.

Secondly, we need to analyse the biomechanics of a patient’s walking, climbing stairs and running style. By studying the articulation of a patient’s body, physiotherapists can garner a clearer understanding of the underlying issues causing extraneous stress on the knees. This enables the practitioner to help the patient reconfigure their gait and rectify the cause of pain. With runners, it is just as imperative to examine the patient’s training load as their running technique.Even minute increases in hill, speed, distance and intensity training can predispose a runner to serious and inhibiting knee injuries.

The positioning of a patient’s feet and ankles as well as their choice of footwear has a marked effect on the conditions of their knees. How you strike your foot when you run or walk – with the heel, midfoot or forefoot – largely influences how and where you bear the impact of your stride.

At Bangalow Physiotherapy, we can fully assess all of the above and help you on your road to recovery.

We all know staying active is essential to maintaining our health and wellbeing. But getting older can pose a little more of a challenge when it comes to your balance and gait. Those over the age of 65 may be wondering ‘how much activity is enough?’

In short, there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. But there are certain types of exercise you can do in your senior years that can help you maintain control over your body and prolong your independence. If the correct form is used—strength, gait, balance and quality of life can all be improved with regular physical activity.

If you suffer from arthritis, it’s essential you avoid any activity that could exacerbate the disease’s progression. Sufferers will need to take extra precautions to avoid the degradation of joints or ligaments that can often be attributed to high-impact activity.

Here’s how you can reap the benefits of exercise in those golden years:

It’s never too late to start exercising

“Good news for all those who’ve spent their lives assigned to the couch.”

For all you late bloomers out there who’ve given up on the idea of getting into shape—this piece of advice is for you. Sure. You’ll need to pay extra attention to your technique and range-of-motion as you get older. But you can ask your physiotherapist about any physical limitations you may have and how to ease into a routine. Your physio will be able to prescribe the right type of exercise to help you maintain a healthy weight, improve function and prevent injury—all at the same time.

What’s more, studies have shown the amazing health benefits of exercise can be enjoyed among all ages, in spite of your former habits. Those who begin their fitness journey later in life will still enjoy the benefits of exercise, including a lowered risk of early death, type 2 diabetes and fall incidence. [1] Good news for those who’ve spent their lives assigned to the couch.

Supervised group core strengthening exercises

“It doesn’t matter how bendy your are or how aerobically-endurant.”

One modality that’s risen to popularity in recent years (and for good reason) is Pilates. This low impact exercise offers a structured form of physical activity that has been shown to improve one’s physical fitness in a much safer manner. Its effect on mood state, quality-of-life and independence in the activities of daily living is significant. [2] And the benefits become even more apparent in the context of a physiotherapy-guided Pilates.

Clinical therapeutic exercise and physiotherapy-guided group exercise is a fantastic introduction to exercise for seniors. It’s also effective in the management and onset of osteoporosis. There’s no need to feel intimidated by these types of classes, as programs are tailored to the individual. When it comes to Pilates, you can begin your practice on a level playing field.

Supervision ensures the utmost safety, and all manner fitness levels are welcomed. It doesn’t matter how bendy your are or how aerobically-endurant. The key to benefitting from Pilates is to integrate your body and mind with the right breathing, control, concentration, precision, fluidity and centralisation. [3] More importantly, your physiotherapist will have a great understanding of the human body and the problems that arise from acute or chronic conditions.

Clinical Therapeutic Exercise

At Bangalow Physiotherapy, we offer several clinical therapeutic exercise programs that offer whole body work-outs using clinical therapeutic exercise, strength and conditioning principles—either one-on-one or in a small group environment. The supervision of our highly-qualified physiotherapists offers a personalised regime that’s safe for all ages, fitness levels and people with certain injuries. See our timetable for classes and more information.

References

1.Saint-Maurice PF, Coughlan D, Kelly SP, et al. Association of Leisure-Time Physical Activity Across the Adult Life Course With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190355. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0355

2. Bullo, V., Bergamin, M., Gobbo, S., Sieverdes, J.C., Zaccaria, M., Neunhaeuserer, D. and Ermolao, A., 2015. The effects of Pilates exercise training on physical fitness and wellbeing in the elderly: a systematic review for future exercise prescription. Preventive medicine, 75, pp. 1-11.

3. Costa, L.M.R.D., Schulz, A., Haas, A.N. and Loss, J., 2016. The effects of Pilates on the elderly: an integrative review. Revista brasileira de geriatria e gerontologia, 19(4), pp. 695-702.

Rebate changes to supervised Group Pilates and Therapeutic Exercise sessions

The Department of Health has made changes to Pilates which could affect your former entitlements. From April 1 2019, Pilates will no longer be rebatable by your health fund. However, group exercise therapy provided by an accredited physiotherapist as part of a patient’s rehabilitation will still be eligible for cover. These amendments follow recent government health insurance reform on natural therapies—including Pilates, yoga, tai chi, aromatherapy, homeopathy, iridology, kinesiology, naturopathy, and reflexology.

Not only that, but physiotherapists providing Pilates services are no longer able to advertise or promote their services as such. Therapeutic Group Exercise sessions using the key principles of Pilates can be advertised for rebate without the use of such terminology—provided they are offered by an allied health care provider as part of an evidence-based rehabilitation program.

How is Therapeutic Group Exercise different from Pilates?

A Pilates workout consists of strength and flexibility exercises performed through precise ranges of motion. High-value group therapy classes are different from regular Pilates in the sense they must be held within the accepted scope of clinical practice, targeting an individual’s treatment and injury needs. Low-impact, therapeutic techniques developed by Joseph Pilates have been applied to a physiotherapist’s understanding of the human body in order to support patients on their road to recovery. This type of exercise, performed within a physiotherapy framework, can help improve strength and posture, treat pain, and minimise the risk of further injury.

Does Bangalow Physiotherapy offer rebatable Clinical Therapeutic Exercise classes?

Our registered physiotherapists currently offer three different types of Clinical Therapeutic Exercise based on key Pilates principles (Mat, Reformer and Gentle)—all of which focus on core stability and correction of movement patterns. These Therapeutic Exercise sessions are rebatable for patients as part of their rehabilitation.

For all new Clinical Therapeutic Exercise attendees, it is required that you have a 30 minutes physical assessment before commencing a Clinical Therapeutic Exercise rehabilitation course. The fee is $85 and is claimable via HICAPS, depending on your individual health fund. A minimum annual review is also required, or more frequently if you have concerns.

Does Bangalow Physiotherapy offer non-clinical Pilates classes?

Casual Group Therapeutic Exercise attendances are possible—provided a space is available and you have already undertaken a pre-assessment with one of our physiotherapists. To ascertain whether or not a casual position has become available, please enquire on the day via telephone. For those fitness enthusiasts outside the realm of recovery, we also offer non-rebatable Pilates classes.

Ask your health fund or physiotherapist about what you can claim on

If you are worried about how these changes may impact your recovery, your best bet is to speak to your insurer about insurance benefits and out-of-pocket costs. Furthermore, you can ask your physiotherapist about which classes are deemed eligible under the new laws or ask industry bodies such as the APA (Australian Physiotherapy Association) about the reforms.

References

The Department of Health, 2019, Private health insurance reforms: Changing coverage for some natural therapies, Australian Government, [Date Accessed: 11/02/19], <http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/private-health-insurance-reforms-fact-sheet-removing-coverage-for-some-natural-therapies>.

The Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA), 2019, PHI natural therapies reform, [Date Accessed: 11/02/19], <https://australian.physio/advocacy/phi-pilates-reform>.

Back pack Safety: getting the right-sized bag and wearing it correctly is crucial for the growing school kid.

Establishing good posture habits from an early age is key in the prevention of acute neck and back pain & injury, as well as long-term spinal problems. Here are some key features for backpack safety:

- Wide / padded shoulder straps worn firmly over the flattest part of both shoulders to avoid pressure on the nerves around the neck and armpits.

- A waist and / or chest strap to help stabilise and distribute the weight to your torso and hips. This helps to avoid overloading the shoulders (kids who carry iPads or laptops, musical instruments, or extra clothing and footwear for after school sports and activities may benefit from such features).

- Keep the heaviest items closest to your back.

- Ensure the maximum weight of the bag doesn’t exceed more than 10-15 % of your child’s body weight.

- Bend both knees and pick up the bag with both hands when putting on the backpack.

- Never wear your back pack on 1 shoulder nor so low that it touches your bottom.

- Try to only carry what you absolutely need to.

Keeping the Balance

Ensuring your child wears the correct sized backpack on both of their shoulders and maintains some level of physical activity in between time spent at the computer and using iPads and other such devices, will help to maintain optimal

posture. This will in turn help to minimise the risk of neck and back ache, headaches and the development of a slumped posture. This combination of a happy, balanced mind and body optimises children’s engagement, motivation, energy and learning potential. If you have any questions or queries regarding your child’s posture or any aches and pains, please come and see us at Bangalow Physiotherapy. We would love to help you.

Some DON’TS for proper posture when using devices and wearing a backpack

With the growing use of screen devices such as iPads & tablets at home and in school, more children are presenting with neck & back pain and slumping postures. This can set them up for chronic pain, headaches and other postural issues later in life unless good habits are established early.

Hints to avoid “iPosture Syndrome”:

- Bring the screen to your eye level. Use a stand or prop to assist.

- Try to maintain an “S” shaped spine to maintain the natural curves of the neck and back. Using a cushion for support can be helpful.

- Avoid tilting your head to the side.

- Change position. Mix it up. Sit, stand, lie down.

- Have frequent rest breaks (ideally every half hour).

- Shrug your shoulders, stretch your arms and body, turn your head and take some big lunge steps to stretch your hips and legs.

Getting back into exercise after an injury

Getting back into shape after suffering an injury is no straight road. While an improvement to your physical condition is important, it’s only the first step towards recovery. For many people, the biggest challenge lies in overcoming those mental hurdles. The fear of reinjury can stop you in your tracks, and it can be difficult to know when it’s safe to start moving again.

Nonetheless, using the correct form protects your body from further injury. Not only that, but it can also help you achieve superior exercise performance and fitness results. There are many benefits to introducing a controlled combination of aerobic, strengthening, and balancing exercises (like clinical pilates). Just make sure you listen to your body (not to mention your physiotherapist) before diving headfirst into your former routine.

Set realistic fitness goals

“Strain yourself, or push too hard, and you’ll run the risk of developing a chronic injury…”

Being sedentary is no way to go about improving your health and wellbeing—but nor is over-exerting yourself. You need to think long-term about your physical goals in order to give yourself the best chance of a full recovery. Commitment to rehabilitation is integral to gaining back your motion and strength, and it’s important to take your physiotherapists’ advice seriously.

Establishing realistic fitness goals minimises the risk of further impairment and helps you adhere to a long-term program. [1] Strain yourself, or push too hard, and you’ll run the risk of developing a chronic injury—posing a far greater threat to your fitness than taking it easy. Even the minimums of exercise can lead us to improvement.

Mentally prepare yourself

“Addressing the psychological aspects relevant to your recovery is essential…”

There’s no doubt a premature rebound can upset the physical recovery, but the psychological implications of pushing too hard, too soon, can also be significant. Research suggests a lack of confidence to be one of the ruling barriers for many people who’ve suffered an injury. [2] A physiotherapist can assist you in becoming actively involved in the rehabilitation process. Addressing the psychological aspects relevant to your recovery is essential to managing your injury and the changes to your routine. [3] Once you’ve learned to confront the blockades of the mind, you can start to enjoy the many physical benefits of exercise, including elevated mood, increased cognitive functioning, and improved self-esteem.

Consult a physiotherapist

“…there’s no blanket timeframe when it comes gaining your strength back.”

Supporting your body with the right technique should be your utmost priority. When it comes to controlled physical outcomes, your physiotherapist will be the best person to make recommendations. They have the clinical reasoning skills needed to provide optimal and individualised exercise therapy in a modified capacity. [4]

Remember, there’s no blanket timeframe when it comes gaining your strength back. If you want to give your body the best chance of a swift recovery, ask your physio to guide you through the movements and correct form. Maintaining good body alignment is integral to supporting your joints and ligaments, as well as rebuilding your strength and improving your mobility.

At Bangalow Physiotherapy, we offer individual rehabilitation and clinical exercise programs to help kick-start your fitness goals. Our programs are specifically designed to help with the improvement, as well as the ongoing maintenance and self-management of your injury. If you have any queries or would like to schedule an appointment, phone 02 6687 2330 or submit an online enquiry.

References

1. Callahan, L.F., Mielenz, T., Freburger, J., Shreffler, J., Hootman, J., Brady, T., Buysse, K. and Schwartz, T., 2008. A randomized controlled trial of the people with arthritis can exercise program: symptoms, function, physical activity, and psychosocial outcomes. Arthritis Care & Research: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology, 59(1), pp. 92-101.

2. Daly, J.M., Brewer, B.W., Van Raalte, J.L., Petitpas, A.J. and Sklar, J.H., 1995. Cognitive appraisal, emotional adjustment, and adherence to rehabilitation following knee surgery. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 4(1), pp. 23-30.

3. Ardern, C.L., Taylor, N.F., Feller, J.A., Whitehead, T.S. and Webster, K.E., 2013. Psychological responses matter in returning to preinjury level of sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. The American journal of sports medicine, 41(7), pp. 1549-1558.

4. Taylor, N.F., Dodd, K.J., Shields, N. and Bruder, A., 2007. Therapeutic exercise in physiotherapy practice is beneficial: a summary of systematic reviews 2002–2005. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 53(1), pp. 7-16.

27.11.2018

Knee Osteoarthritis

What is Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis (OA) is joint issue most commonly affecting a majority of the population by the age of 65 years-old (Felson, 1988). Osteoarthritis can affect any joint in the body, but one of the most common areas affected is the knee.

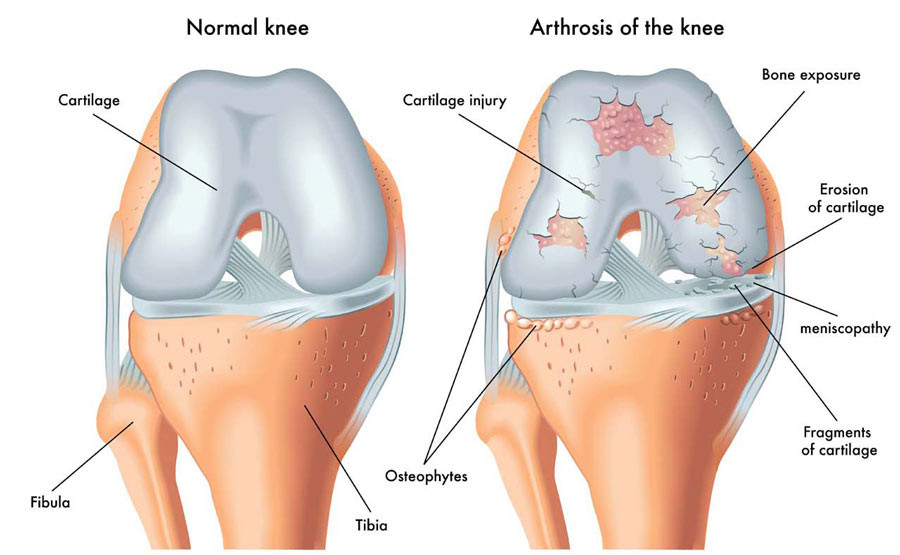

Often described as general wear-and-tear, osteoarthritis involves the degeneration of the bony surfaces of the knee:

- The cartilage covering degenerates to expose underlying bone

- Bony spurs (known as osteophytes) form on the inside and edges of the joint

- Ligaments and the meniscus may also deteriorate as a result being rubbed between the rough surfaces

(Figure 1 – retrieved 23.11.18 from https://therapia.com/conditions/physiotherapy-for-osteoarthritis/)

This degeneration can limit movement and cause significant pain resulting in disability as the disease progresses.

Signs & Symptoms:

- Generally a slow, gradual onset of symptoms

- Deep aching pain felt felt at rest

- Increased pain with weight-bearing and with movement

- Stiffness with movement

- Crepitus (felt as creaking sensations within the joint)

- Swelling

- Deformity

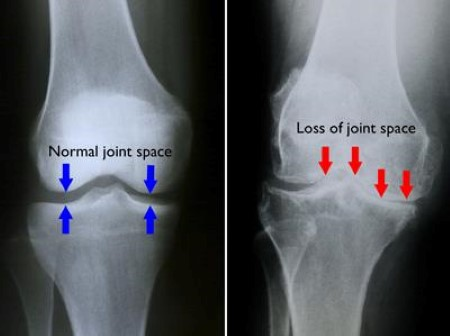

- Loss of joint space as seen on an x-ray (Fig. 2)

(Figure 2 – retrieved 23.11.18 from https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/arthritis-of-the-knee/)

Causes:

- Being overweight, which increases the force on the knee, causing more damage to the joint

- Excessive and repeated bending forces through the knee over a long period of time

- History of injury or insult to the knee

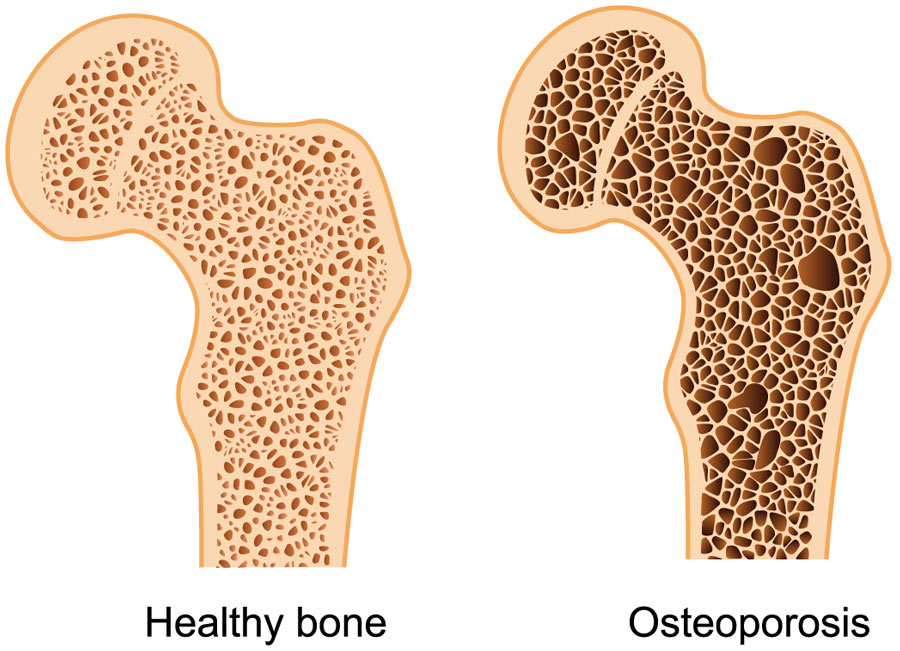

What’s the difference between Osteoarthritis and Osteoporosis?

Whilst the terms “osteoarthritis” and “osteoporosis” are often used interchangeably, they are not to be mistaken as the same condition. Osteoarthritis affects the particular surfaces of a joint as previously explained. Osteoporosis affects the inner porous matrix of the bone. Osteoporosis is the resulting dysfunction of the rate that new bone is deposited due to age related issue related to hormones, genetics, age or decreased physical activity. This lack of new bone being deposited means the bone becomes fragile and is susceptible to breaking more easily. Unlike osteoarthritis, there are no symptoms of pain or loss of function in the development of osteoporosis until a fracture occurs.

(Figure 3 – retrieved 23.11.18 – https://therapia.com/conditions/physiotherapy-for-osteoporosis/)

Treatment:

Treatment of osteoarthritis is directed at managing symptoms and enhancing or maintaining range of motion and mobility.

Conservative management

- Lifestyle change such as avoiding aggravating and high impact activities, as well as lowering body weight through diet and physical activity will reduce the forces placed through the joint, positively influencing pain and further aggravation of the joint.

- Medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory or other pain relief may be prescribed by your doctor depending on the patient’s medical history.

- Heat or ice may help to reduce the sensation of pain.

- Braces and bands may provide the knee with a subjective feeling of support.

Physiotherapy treatments focusing on improving range of motion and releasing soft tissue around the knee can positively influence symptoms. Also implementing a tailored exercise program aimed at improving the strength, flexibility and proprioception (neuromuscular feedback of where the knee is as it moves) of the knee has been shown to be one of the most effective ways to reduce painful osteoarthritis symptoms, improve range and subsequently improve quality of life (Fransen & McConnell, 2008). Hydrotherapy has been demonstrated to also improve pain (Silva et al, 2008) and reduce load through the knee whilst weight-bearing, allowing the individual the opportunity to be physically active.

Surgery

- A total knee replacement may be necessary for suitable patients who have severe osteoarthritis and have genuinely attempted conservative management for many months with no improvement or worsening of symptoms.

If you experience osteoarthritis related knee pain or are aware of your progressing osteoarthritis and would like to get on top of your symptoms before they get on top of you, get in touch with a physiotherapist to start your journey of maintaining pain-free mobility throughout life.

References:

Felson; D.T. (1988) Epidemiology of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Epidemiologic Reviews, Volume 10, Issue 1, Pages 1–28

Fransen, M., & McConnell, S. (2008). Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (4).

Silva, L. E., Valim, V., Pessanha, A. P. C., Oliveira, L. M., Myamoto, S., Jones, A., & Natour, J. (2008). Hydrotherapy versus conventional land-based exercise for the management of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. Physical therapy, 88(1), 12-21.

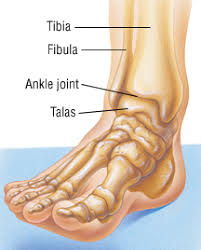

Anatomy of the Ankle & Foot

The anatomy of the ankle and foot area is quite complex. The ankle (a.k.a. the talocrural joint) is formed in the region where 3 bones meet: the tibia (or shin-bone), the fibular and the talus (fig. 1). The the bony knobs on either side of your ankle are formed by the tibia and fibula. These are called the medial malleolus (tibia) and lateral malleolus (fibula). The talus acts to transfer weight from the leg onto the bones in the feet, including the heel bones (calcaneus). The joint between the talus and the calcaneus is called the subtalar joint.

(Figure 1 – The Talocrural Joint – retrieved 23/10/18 from https://www.drugs.com/health-guide/ankle-fracture.html)

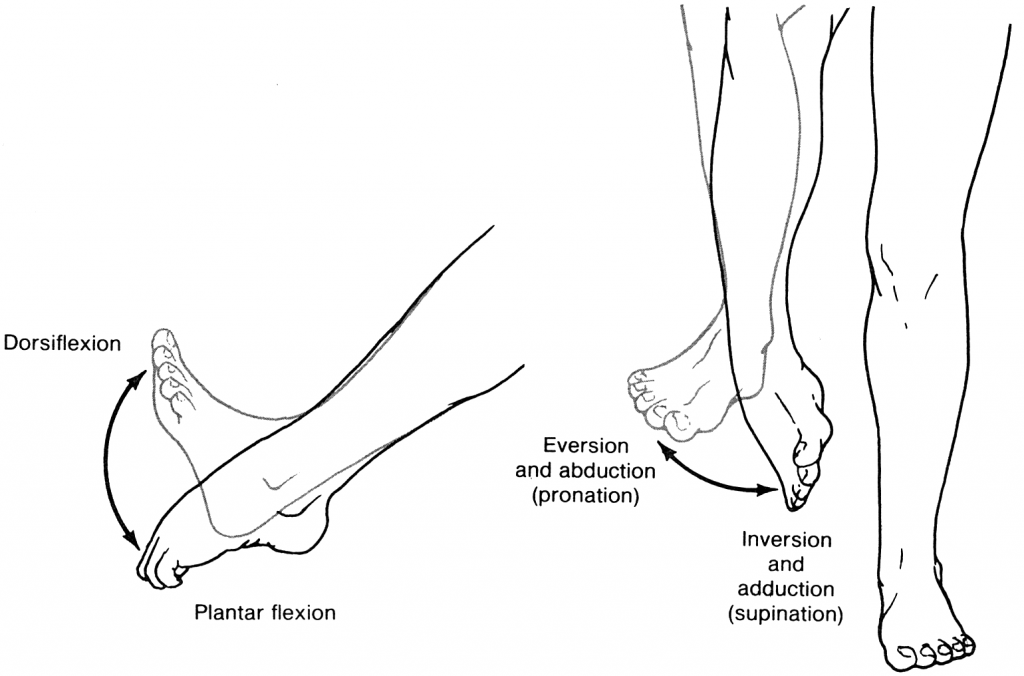

Movements created at the talocrural joint include plantar flexion and dorsiflexion. Sideways movements, known as inversion (supination) or eversion (pronation), come from the subtalar joint. These movement are demonstrated in the figure below.

(Figure 2 – Ankle Movements. Retrieved 23/10/18 from https://accessphysiotherapy.mhmedical.com/Content.aspx?bookId=965§ionId=53599846)

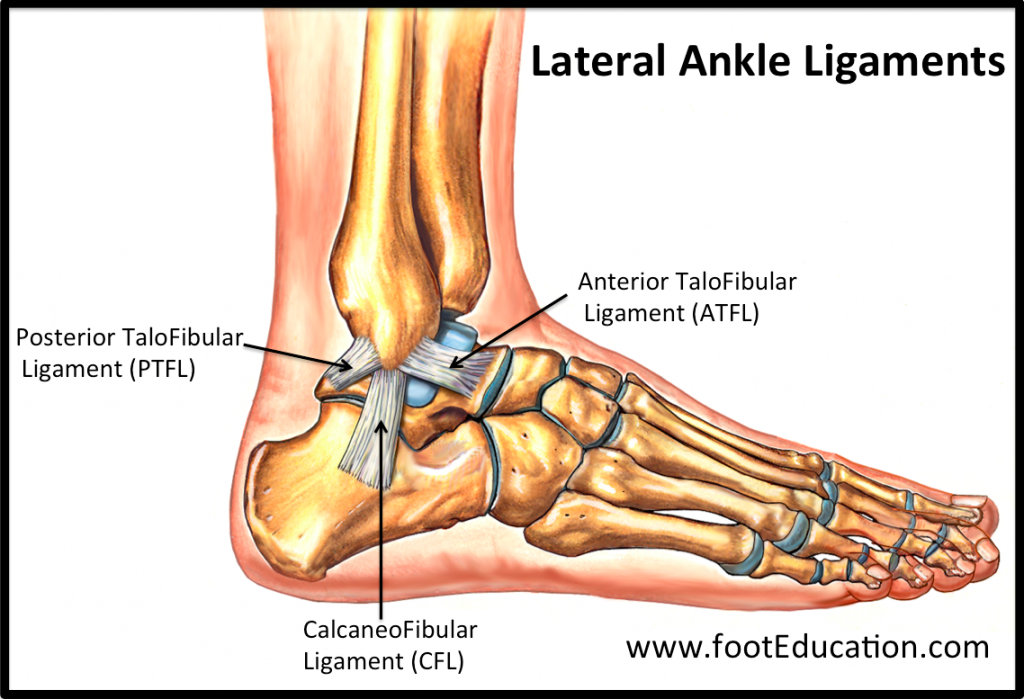

Ligaments & Sprains

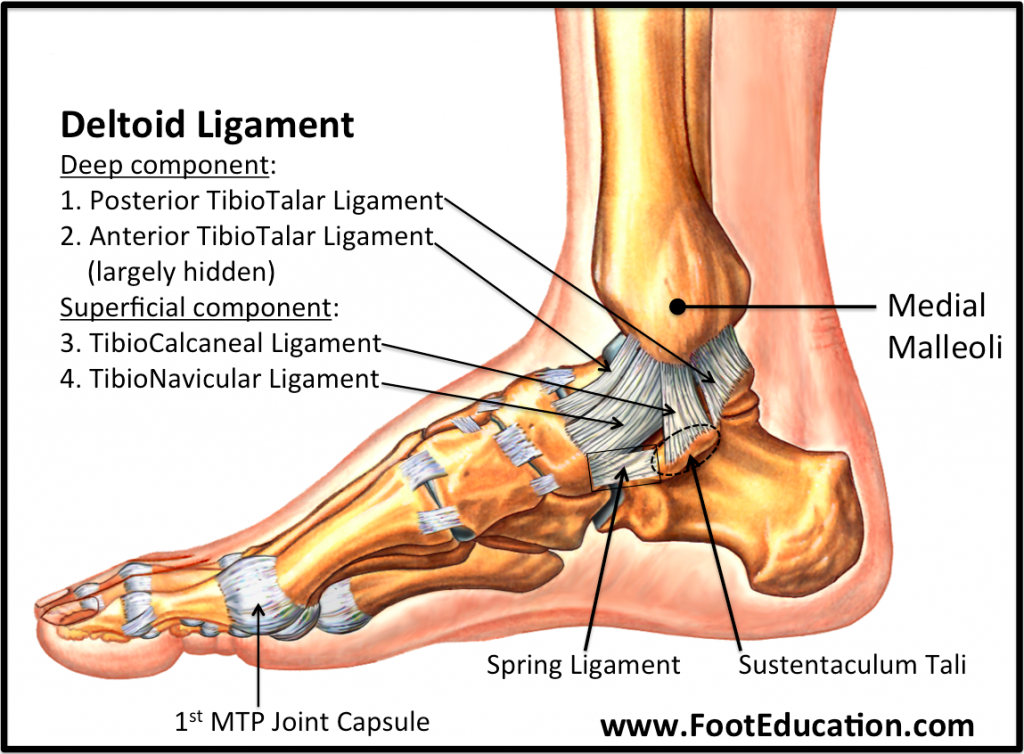

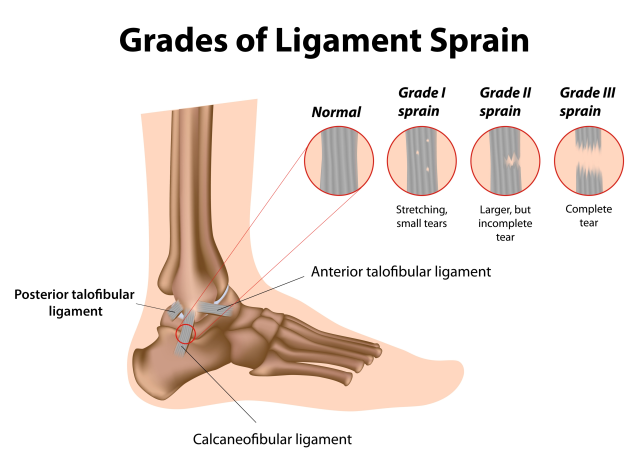

The ankle is secured by surrounding ligaments which support the joint. Some of these ligaments are either partially or completely torn when the ankle stretches beyond its normal range of movement (shown above). This damage to the ligament is called a sprain. The most common non-contact injury seen at the ankle occurs when someone “rolls” into inversion, stretching the ligaments on the outside of the ankle (Fig 3). This is known as an inversion injury or lateral ankle sprain. Whilst the medial ankle ligaments (Fig.4) can also be sprained through an eversion injury, these types of injuries are less common and often are a result of a more traumatic or contact-related accident.

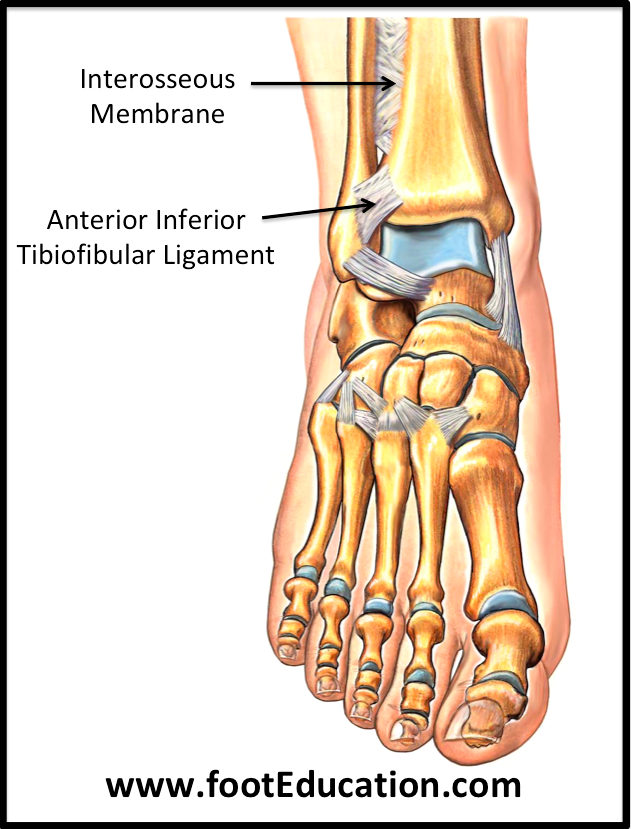

Another less common ankle sprain occurs between the tibia and fibular (Fig. 5), known as a high ankle sprain.

(Figure 3 – Lateral Ankle Ligaments. Retrieved 24/10/18 from https://www.footeducation.com/page/ligaments-of-foot-and-ankle-overview)

(Figure 4 – Medial Ankle Ligaments. Retrieved 24/10/18 from https://www.footeducation.com/page/ligaments-of-foot-and-ankle-overview)

(Figure 5 – High Ankle Ligaments. Retrieved 24/10/18 from https://www.footeducation.com/page/ligaments-of-foot-and-ankle-overview)

Sprains are categorised by the severity of the damage done to the ligament, as demonstrated in Figure 6 below. Higher grades are usually associated with an increase in swelling, redness, pain, heat and loss of function (the 5 cardinal signs of inflammation – mentioned and further explained in the inflammation post below). Grade III sprains often result in joint instability/laxity. Fractures within the ankle may also be possible, depending on the severity of the sprain.

(Figure 6 – Ligament Sprain Grades. Retrieved 26/10/18 from https://www.google.com.au/url?sa=i&source=images&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwifh9bng6PeAhVCXCsKHdwgAQkQjxx6BAgBEAI&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.painmanagementdoctornyc.com%2Fnyc-ankle-sprain-specialist-sports-medicine-doctors%2F&psig=AOvVaw0QQISenbpHg3UZuWPYGAdK&ust=1540444976548806)

Treatment

Immediate

Historically, ankle sprains were initially treated with the R.I.C.E (Rest, Ice, Compression & Elevation) protocol. This has now evolved to M.C.E (Movement, Compression, Elevation) as a result of more research (further explained in the below post regarding inflammation). While ice may be applied immediately after the injury to help to numb the area, the emphasis of immediate management should be on applying compression to the joint, as well as elevation to help mediate swelling and safe movement, and avoid loss of function. During this phase, your physiotherapist can help to establish a safe movement pattern, unloading strategies, as well as potentially apply LAZER to assist with the management of pain and swelling.

Later

After the first week, the inflammatory stage will have ceased and the ligaments will be attempting to heal as the swelling dissipates. In this phase, the focus will be on regaining movement in a safe and gradual way. Your physiotherapist will apply manual techniques such as joint mobilisations, soft tissue release, oedema control and prescription of specific exercises aimed at reducing stiffness and improving movement within the joint. During this time, attention may also be paid to correct any compensatory mechanisms that may have arisen as a result of the injury.

It is always best to seek guidance from a trained physiotherapist to ensure a safe and appropriate recovery from an ankle sprain of any grade.

Recent Comments